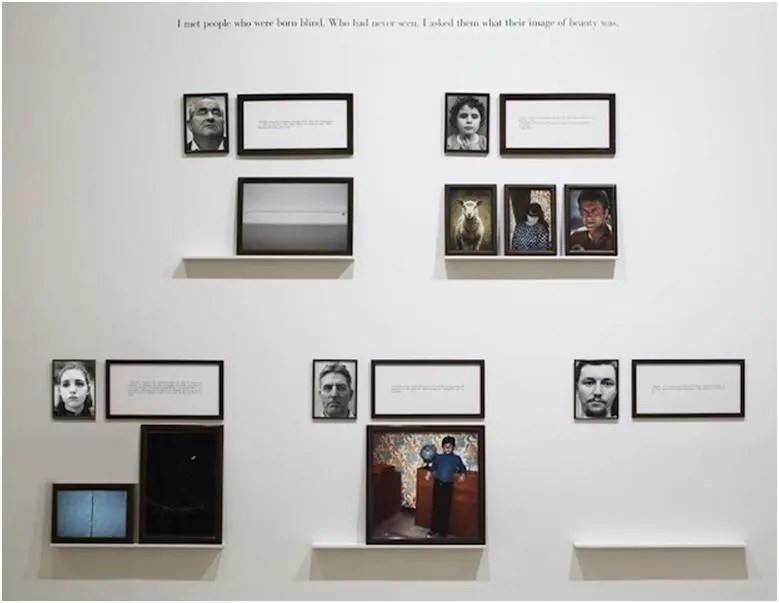

We are delighted to share the runner-up essay from this year’s Brian Darling Memorial Essay Prize Competition, organised by the Association for the Study of Modern and Contemporary France (ASMCF). Written by recent John’s graduate Maisy Hicks, the piece explores artist Sophie Calle’s exhibition d’Aveugles (The Blind), in which Calle asked blind participants what they considered beautiful. Maisy’s essay reflects on the implications of such a project in an ocularcentrist culture, where sight dominates the hierarchy of the senses, and where beauty is often framed through patriarchal norms.

Sophie Calle’s Aveugles is a collection of photographs and accompanying texts that together compose a delicate paradox. The paradox lies in the very structure of the work: each participant, blind from birth in the section this essay focuses on, is photographed, asked to describe what they believe to be beautiful, and then represented again through a photograph of this described object or concept. At the heart of this gesture is a tension between presence and absence, visibility and invisibility. Calle’s use of photography, a fundamentally visual medium, to convey the inner aesthetic world of individuals without sight complicates our understanding of perception and challenges the primacy of the visual in the construction of beauty. This paradox is further compounded by the nature of the photographic image itself. As Marianne Hirsch asserts, photographs are not only indexical records of the real but also mimetic renderings, at once rooted in materiality and suggestive of an interpretive gaze (115). Photography, then, opens a dual space: one that captures the ‘real’ object and one that constructs its image for a viewer. In Aveugles, this duality takes on new weight. The blind subjects cannot access the final image; the visual record exits exclusively for the sighted viewer. The work becomes an encounter shaped by absence, where the subject’s account of beauty is filtered through a medium they cannot themselves experience, and where the viewer must reckon with the disjunction between memory and vision. It is within this disjunction that embodied perception emerges as a central concern. What does it mean to feel beauty rather than see it? What happens when beauty is remembered, imagined, or sensed through touch, smell, sound, or emotional resonance? Calle’s work does not answer these questions so much as it invited the viewer to dwell within them. The accounts given by her blind subjects often return to a shared motif: nature. Whether described directly or through metaphor, the natural world surfaces repeatedly in their evocations of beauty. This recurrence, I argue, is more than incidental. Nature, in Aveugles, becomes a site of sensory knowledge, an embodied archive that resists the ocularcentrism of Western aesthetic thought. In this way, Aveuglesperforms a quiet but radical feminist gesture. It reconfigures both the landscape and the body as sites of knowing, moving away from detached observation and toward lived, affective experience. By foregrounding the voices and sensory worlds of blind participants, Calle unsettles dominant narratives that conflate vision with truth, and beauty with visibility. The work invites us to imagine a perceptual politics in which memory and touch as much, if not more, than sight. This essay will explore how Aveugles stages a dialogue between sensory perception, nature, and feminist thought. Drawing on ecofeminist critiques, particularly Val Plumwood’s call for the convergence of environmental and justice-based concerns (122), I will examine how Calle’s work reframes the natural world not as an object of passive contemplation but as a textured, embodied space shaped by marginalised sensory experience. As Stacy Alaimo notes, marginalised bodies, including those of individuals with disabilities, exist in a fraught relationship with dominant Western conceptions of nature, often positioned as both outside and subordinate to it (19). In Calle’s work, this marginality becomes a source of insight, inviting a more entangled, inclusive, and embodied ecology of belief.

In Aveugles, Sophie Calle assembles more than a collection of reflections on beauty; she curates a series of remembered landscapes, ones held not through sight, but in the body. When asked what they find beautiful, Calle’s blind participants often turn to the natural world: a young boy states ‘Le vert, c’est beau. Parce que chaque fois que j’aime quelque chose, on me dit que c’est vert. L’herbe est verte, les arbres, les feuilles, la nature… J’aime m’habiller en vert.’ His knowledge of the colour green comes from his intrinsic love of the natural world, he haptically engages with the colour through this love, choosing to dress himself in green. Despite his not seeing the natural elements that inform his love of the colour, his sensory perception of this aesthetic beauty remains strong. These are not visual descriptions in the traditional sense but sensorial recollections, fragments shaped by touch, memory, sound, and atmosphere. What emerges is not a catalogue of natural imagery, but what Roberta Culbertson terms ‘body memories,’ ‘the branching veins that feed the self’ (182). Here, landscape is not something external and observable, but internal and affective, an embodied archive of sensation. These recollections resist stability. They echo what Culbertson calls a ‘homesickness for an experience, even a place […] that cannot be otherwise explained’ (177). A longing for something that once registered in the body but now exists only as a trace. This reframing of memory as sensory rather than visual opens a powerful feminist lens. As Katharina Schramm argues, memory can be understood as a process, ‘perhaps perpetual’ (9), rather than something that can be conclusively archived or mastered. Nature, in this framework, is not passively observed, but carried, saturated with what Schramm called the entangled meanings of ‘nature, culture and history’ (13-14). Calle’s approach preserves this instability. Her photographic representations do not offer resolution. Instead, they foreground disjunction. The images do not visually affirm the participants’ memories so much as expose the failure of the visual to fully translate the felt. This is where the tension between the participant’s sensory recollection and Calle’s visual response becomes most striking. For instance, the woman on page 34 who recalled ‘cette vue, depuis mon balcon, en Haute-Savoie’. Calle’s corresponding image gestures towards a horizon of trees, but the gap between image and embodied memory remains unbridged. The photograph acts not as confirmation, but as provocation, a visual reminder of the viewer’s distance from the speaker’s experience. In this way, Calle aligns Robert K. Shope’s view that memory should not be reduced to a retrievable visual ‘trace,’ and that ‘nothing about the causation of remembering can be inferred’ from such traces alone (318). Instead, what Aveugles performs is a quiet disruption of visual logic, a preparation for an alternative perceptual framework. It is precisely this disruption that leads us to reconsider how vision has come to dominate ways of knowing, and how feminist and disability discourses might offer a different way forward. If these remembered landscapes resist visual mastery, then so too must our understanding of perception. Calle’s work thus moves us, not just from image to memory, but from seeing to sensing, a transition that invites further interrogation of the politics of sight.

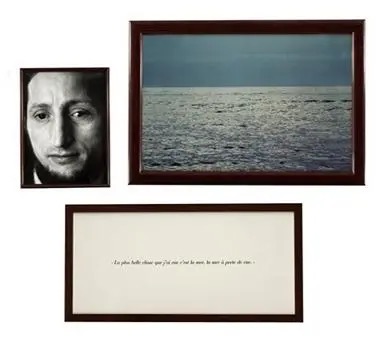

The Western philosophical tradition has long upheld the vision as the dominant mode of knowledge. Even Cartesian rationality embeds the visual in its very structure (Plumwood 122), reinforcing a logic in which sight equates to truth and understanding. This has shaped not only the way we engage with knowledge but also how we perceive and interact with the natural world. In Calle’s Aveugles, however, we see an interruption of this legacy. The testimonies of the blind participants foreground landscape as an archive of embodied memory. Through their multisensory descriptions of beauty, they prompt the sighted viewer to confront their own visual privilege. The inclusion of a photograph of each described object reflects this tension. As Wendy Bellion notes, ‘most art objects, after all, are designed to be looked at’ (22), and it may seem natural that Calle, working within a visual medium, adheres to this expectation. Yet these images function less as bridges than as barriers. They become, in Martin Jay’s terms ‘dead objects’ (312), visual relics that expose the phenomenological gap between sighted and non-sighted experience. In doing so, Calle’s work gestures toward the need for a feminist reimagining of perception, one that does not default to the visual. Resistance to such a shift stems, in part, from ableist cultural imaginaries that reduce blindness to a kind of existential absence. As Paterson observes, blindness is often ‘characterised by this fear of darkness without end’ (164), evoking anxieties about being cutoff from beauty and experience. This logic positions the blind subject in a space of lacking, presumed incapable of engaging with the world on equal terms. Yet Calle’s work actively resists this construction. On page 10, one participant states: ‘La plus belle chose que j’ai vue, c’est la mer, la mer à perte de vue.’ Though blind, he places himself within the field of vision, suggesting that his experience of the sea is no less vivid or profound. His catachrestic statement illustrates what Bence Nanay terms ‘perceptual phenomenology’ (263): a mode of encountering the world rooted in the senses defined by but not confined to the visual. This complicated the assumption that vision is the privileged sense through which beauty must be accessed. To meaningfully engage with the ‘sins of ocularcentrism’ (Jay 308), we must also interrogate how vision has historically been tied to mastery, detachment, and control; all hallmarks of patriarchal logic. These dynamics marginalise blind individuals and contribute to the objectification of nature itself. In this way, the experiences of Calle’s participants echo those of the natural world under patriarchal capitalism: devalued, dominated, and distanced. The absence of visual mastery does not diminish these individuals’ capacity for perception; rather, it reveals the constructed nature of visual authority. What we choose to ‘see’ is shaped by attention (Nanay 264), and Calle’s work reminds us that perception is never neutral. The repeated use of catachresis in Aveugles, where blind participants employ visual metaphors, further destabilises the visual hierarchy. These figurative expressions suggest that seeing need not be literal but can signify a broader field of embodied knowing. The common stereotype of the blind as being ‘rewarded by a compensatory gift of insight’ (Linett 28-29) stems from a misrepresentation: a need to explain sensory difference through mystification. Yet this very stereotype reveals how deeply entrenched the visual bias remains, and why alternative epistemologies are urgently needed. Vivian Sobchank reminds us that anecdote can serve as ‘an antidote to objective accounts of the body’ (7), offering representations more faithful to lived, embodied realities. For those without sight, the haptic world unfolds ‘successively over time’ (Paterson 172), generating a temporal, tactile mode of perception that is no less rich or attentive. In Aveugles, these haptic experiences of nature challenge the dominance of the visual and invite us to reimagine what it means to know, to remember, and to feel beauty.

If Aveugles reveals a connection between the natural world and embodied sensory experience, it is not to suggest that this link is innate or mystical, but rather structurally and politically situated. The participants’ descriptions of beauty return repeatedly to nature not as picturesque backdrop but as something inhabited. These recollections mark nature as a space of both intimacy and estrangement, spaces that are felt, remembered, and mourned. Such articulations resonate with ecofeminist understandings of the body as entangled within ecological systems of power and violence. As Greta Gaard argues, ecofeminism argues “androcentrism” (40), a mode of thinking that naturalises hierarchies, positioning women, disabled people, and nature as passive or in need of control. This is not a metaphorical alignment but a material one. Both the blind body and the natural world are subjected to erasure under systems that equate value with productivity and domination. Within this framework, memory itself becomes a site of resistance. The participant who recalls a ‘paysage désolé’ (Calle 23), noting that ‘la photo ne rendra pas le vent,’ gestures toward the limitations of representational logic. The wind, the feeling of vastness, the subtle fear of stepping on a flower, these are not images, but sensations carried in the body. Their resistance to visual capture parallels the natural world’s resistance to enclosure and domestication. As Roberta Culbertson writes, trauma and extremity ‘explode the motion of memory into a series of ‘body memories’’ (178), which are not only experienced but stored in the sensory fabric of the self. This notion resonates strongly in Aveugles, where landscape becomes not just the setting of memory but its expression, unfolding in haptic, aural, and proprioceptive modes. These recollections of nature do not stand outside culture but emerge from within its most violent structures. The repeated association of beauty with affective and ‘unseeable’ natural scenes reminds us that these participants speak from within a system that renders both blindness and the environment as othered. As Swanson notes, this is the legacy of dualistic thought: ‘women/nature/race’, and indeed people with disabilities, are rendered as objects to be managed or transcended, never as epistemic agents (87). Calle’s work does not impose coherence on these accounts but allows their resistance, their embodiedness to remain unresolved. This refusal to stabilise memory is, in itself, a feminist gesture. And yet, it is vital to remain wary of how easily structural marginality can be reabsorbed into essentialist narratives. Buckingham reminds us that those ‘distinguished by difference’ (147) are often perceived through a lens of naturalisation, a mode of thinking that conflates structural position with innate disposition. To suggest that the blind are somehow closer to nature is to risk refining the very dualisms ecofeminism seeks to undo. What Aveugles offers instead is an ecological politics of relation. A reminder that to remember beauty through the body is not to embody purity, but to navigate shared systems of vulnerability, perception and resistance.

In Aveugles, blindness is not simply the absence of sight, it is a confrontation with cultural assumptions about embodiment. Calle’s project stages a sensory dissonance. It places the sighted viewer into proximity with forms of knowing that resist visual logic, centring disability not as lack, but as epistemic difference. As explored earlier, the participants’ sensory recollections of the natural world reveal deep interconnections between marginalised embodiment and landscape. But it is equally important to consider how disabled narratives operate in relation to nature’s supposed opposite: what Jenny Morris calls the ‘public world’ (66), a realm defined by productivity. This world, built on a logic of manual function and normative time, often excludes disabled experiences altogether, or folds them in only as objects of scrutiny. Morris writes that ‘our standpoint [is] excluded from cultural representations’ (66), a process reinforced by how disability is treated within research and institutional discourse. Too often, people with disabilities are rendered subjects of knowledge, rather than knowledge-holders themselves. Aveugles risks echoing this tradition, it is a visual project centred on the experiences of individuals who cannot access the final product. Yet this very paradox invites critical reflection: it raises the question of who art is for, and whether feminist aesthetic can account for non-visual experience. Feminist disability voices do not interrupt feminism, they refine it. They are, as Morris argues, a ‘sane response to the oppression we experience’ (67), and demand not only cultural inclusion but a restructuring of how we think about embodiment, value, and autonomy. As Susan Wendell observes, this begins with resisting the ‘cultural insistence’ on bodily control and standardisation (114). Disability troubles the supposed universality of the able-bodied experience. In a society where labour defines worth, those deemed unfit to work are rendered socially invisible. The disabled body becomes a body ‘out of time,’ misaligned with the rhythms of capitalist production. This dispossession is visible in early 20th-century frameworks, such as the 1931 study by the Association des Industriels de France, which equated blindness with death, calculating its cost by labour value (The Science News-Letter374). Here, disability is not just devalued; it is dehumanised. Sight, meanwhile, is imbued with epistemological privilege. Hans Jonas describes vision as a ‘widening of the horizon of information’ (511), a metaphor that encodes the hierarchy of senses. The ‘horizon’ itself implies foreknowledge and mastery, qualities culturally denied to blind individuals. As Jonas notes, ‘knowledge at a distance is tantamount to foreknowledge’ (519), rendering non-visual ways of knowing secondary. In response, feminist disability theorists urge us to dismantle the structures that exclude. A reframing of bodily difference becomes a necessity, Kim Q. Hall insisting that ‘liberation requires transforming society to include diverse embodiments’ (XI). This transformation is not symbolic, it is material. As Wendell argues, a truly inclusive society must ‘provide the resources that would make disabled people fully integrated and contributing members’ (110). Calle’s Aveugles, then, is not simply an artistic paradox, it is an opening into this necessary work of reimagining power and inclusion.

Sophie Calle’s Aveugles invites us to reconsider what it means to remember and to feel beauty beyond the visual. The work challenges the authority of sight by foregrounding the haptic and emotional experiences of blind participants. In doing so, it opens a space for what Constance Classen describes as the ‘nurturing of multisensory aesthetics’ (159), a mode of engagement that privileges embodied memory over visual mastery. The participants’ recollections of beauty, often rooted in nature, offer not only personal testimony but a structural critique. As Val Plumwood argues, ‘control over and exploitation of nature contributes to […] control over and exploitation of human beings’ (22). The alignment of disabled bodies and natural landscapes in Aveugles exposes this shared subjugation under a logic that privileges productivity and visibility. Yet Calle’s work does not romanticise this marginality; it stages it as tension. The participants’ memories resist capture, photographically and culturally. Vivian Sobchank reminds us that disability represents ‘radical signs of the “matter” of human beings as out of human control” (289). In Aveugles, this loss of control becomes a generative disruption. The photographs do not resolve memory into image; they destabilise it, revealing how representation can fracture rather than complete perception. This refusal of visual coherence is not a failure; it is a feminist aesthetic strategy. Through this sensory dissonance, Calle’s project becomes more than an exploration of blindness. It becomes a meditation on perception as political terrain, where dominant structures of knowing are revealed as partial and exclusionary. As Plumwood writes, ‘environmental issues and issues of justice must increasingly converge’ (22). Calle’s work enacts this convergence, revealing how the epistemic devaluation of blindness parallels the ecological degradation of the natural world, both cast as others, both rendered mute under systems of mastery. Ultimately, Aveugles reclaims the landscape as a feminist and relational archive. One that resists domination and centres marginalised embodiment as a site of knowledge. It reminds us that to perceive is not simply to see, but to feel and to remember. In this way, Calle offers not just a critique of vision, but an invitation to perceive differently, to listen carefully, and to understand that beauty, like knowledge, is always already shaped by power.

Photos provided by Maisy Hicks.

Works Cited

Alaimo, Stacy. Exposed Environmental Politics and Pleasures in Posthuman Times. University of Minnesota Press, 2016.

Bellion, Wendy. “Vision and Visuality.” American Art, vol. 24, no. 3, 2010, pp. 21-25.

Buckingham, Susan. “Ecofeminism in the Twenty-First Century.” The Geographical Journal, vol. 170, no. 2, 2004, pp. 146-54.

Calle, Sophie. Aveugles. 1st ed., Actes Sud, 2011.

Classen, Constance. The Museum of the Senses: Experiencing Art and Collections. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2017.

Culbertson, Roberta. “Embodied Memory, Transcendence, and Telling: Recounting Trauma, Re-Establishing the Self.” New Literary History, vol. 26, no. 1, 1995, pp. 169-95.

“Death and Loss of Sight Are Held to Be of Equal Value.” The Science News-Letter, vol. 19, no. 531, 1931, pp. 374.

Gaard, Greta. “Ecofeminism Revisited: Rejecting Essentialism and Re-Placing Species in a Material Feminist Environmentalism.” Feminist Formations, vol. 23, no. 2, 2011, pp. 26-53.

Hall, Kim Q. “Feminism, Disability, and Embodiment.” NWSA Journal, vol. 14, no. 3, 2002, pp. vii-xiii.

Hirsch, Marianne. “The Generation of Postmemory.” Poetics Today, vol. 29, no. 1, 2008, pp. 103-28.

Jay, Martin. “The Rise of Hermeneutics and the Crisis of Ocularcentrism.” Poetics Today, vol. 9, no. 2, 1988, pp. 307-26.

Jonas, Hans. “The Nobility of Sight.” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, vol. 14, no. 4, 1954, pp. 507-19.

Linett, Maren. “Blindness and Intimacy.” Mosaic: An Interdisciplinary Critical Jounral, vol. 46, no. 3, 2013, pp. 27-42.

Morris, Jenny. “Feminism and Disability.” Feminist Review, no. 43, 1993, pp. 57-70.

Nanay, Bence. “The History of Vision.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, vol. 73, no. 3, 2015, pp. 259-71.

Paterson, Mark. “Looking on darkness, which the blind do see: Blindness, Empathy, and Feeling Seeing.” Mosaic: An Interdisciplinary Critical Journal, vol. 46, no. 3, 2013, pp. 159-77.

Plumwood, Val. Feminism and the Mastery of Nature. 1st ed., Routledge, 1993.

Schramm, Katharina. “Landscapes of Violence: Memory and Sacred Space,” History and Memory, vol. 23, no. 1, 2011, pp. 5-22.

Shope, Robert K. “Remembering, Knowledge, and Memory Traces.” Philosophical and Phenomenological Research, vol. 33, no. 3, 1973, pp. 303-22.

Sobchank, Vivian. Carnal Thoughts: Embodimemt and Moving Image Culture. University of California Press, 2004.

Swanson, Lori J. “A Feminist Ethic That Binds Us to Mother Earth.” Ethics and the Environment, vol. 20, no. 2, 2015, pp. 83-103.

Wendell, Susan. “Towards a Feminist Theory of Disability.” Hypatia, vol. 4, no. 2, 1989, pp. 104-24.