Rob Gomulak reflects on the college field trip to York.

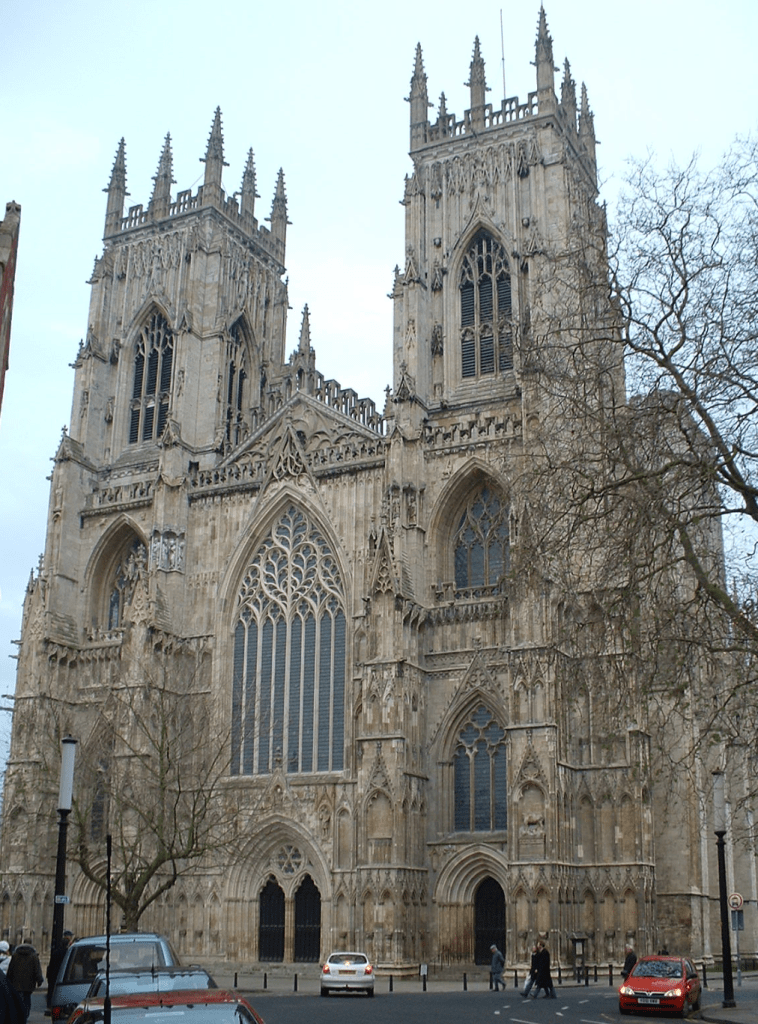

On a sunny Saturday, the St. John’s College Mentor program gathered for a field trip to York. Most of the attendees were international students, like myself, from all corners of the world, including China, the USA, Malta, India, Bulgaria and beyond. After a short bus trip through the North Yorkshire countryside, passing throngs of vibrant green rolling hills newly touched by the approaching Spring, the ancient stone walls of medieval York began to manifest. Felipe, a St. John’s PhD student and Resident Tutor from Colombia, led our group through the historic landmarks dotted around central York, delivering incredible bits of trivia that added untold depth to our tour. Felipe knew a bit about everything, from the York Minster, which boasts one of the oldest stained-glass windows in the UK, to the Shambles, which derives their iconic architecture from obscure medieval tax laws. Felipe was there to guide us through the history and uniqueness of this charming city.

In the tented Shambles Markets, which bear a strong resemblance to Durham’s own weekend market in the square, sellers were comprised of the expected dropshippers and car boot salespeople, but every so often, a stall selling craft jewellery, fresh-baked baklava, and treasures not available anywhere else would manifest.

At the nearby food trucks, I bought a burrito. A bold move, especially as a Texan who knows better and has been time and time again deeply offended at what the UK typically offers as Mexican cuisine. To my surprise, it tasted like home and spices that I have had trouble tracking down anywhere on this island. The truck’s recipes were homemade, and their food was, in my opinion, in the running against anything produced north of Laredo. In that lunchtime, we all had a brief chat about our gratefulness in being on this side of the pond.

Even the woman who sold me a crumble with custard, arguably one of the most British foods in existence, spoke with an Eastern European accent and proudly displayed a Ukrainian flag pin on her apron. Everywhere in the Shambles Markets were people like us, people who came to the UK looking for something, chasing a dream or a fever, wanting something better. There were, however, several stalls that were conspicuously empty, and as I passed, I wondered if there should be a person sitting there, selling me something delicious and homemade, and I wondered where they were; just down the block, further still, or somewhere farther than we could ever imagine.

On Shambles Street itself, entrenched shops battled with throngs of tourists, the tourists vying for space, the shops vying to sell their upcharged goods. I have yet to see the tourists emerge victorious. There are plenty of characteristic little stores selling things you would never need but only want, exquisite perfumes that smell remarkably similar to each other, a ceramic ghosts shop which constantly boasts a queue at least two hours in length, confectionary shops that I’m sure are lovely but bear striking resemblance to the prior three sweets shops I’d passed in the last block, and so on. But it’s all fun, and it makes you feel like a part of something fantastical, like a secret troll market or a magic bazaar.

On Museum Street leading to the York Minster, which, to be candid, none of us had the funds to enter, but admired from the outside, there is a burgundy-red building which stands in stark contrast to the monuments and gothic architecture that surround it. It is an antique mall, and the first building Felipe had no trivia for, or any knowledge of at all. We ventured inside, each of us in our own way wanting to examine old trash. But that’s not at all what we found. In the cases nearest the door were

Grecian kylixes, lapis amulets from Ptolemaic Egypt, Han dynasty pottery, spearheads, effigies, jewellery from time immemorial and corners of the globe eternally scavenged. Was it real? The archaeologists of our troupe, myself included, thought they looked real enough.

The one object that is fixed in my mind is a sarcophagus mask from Middle Kingdom Egypt. Its nose is broken, the paint has faded with the millennia, but within its eyes are echoes of Empire and Empire again, and for the low price of 1,700-odd pounds you too could own the weathered face of a child, sibling, parent, who was so mourned their visage was likened upon their coffin. My hands felt heavy and wet and red, like I had touched the walls of this building when the paint was still drying. In browsing the plundered goods that never made it to the British Museum, a crowd of international students, immigrants all, beheld a stolen face for sale.

When we got back on the bus, we were all tired in a way that we couldn’t convey. We joked and talked, each of us had a wonderful time, a great day by any measure, but the sun was setting. We thought of home.

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons