Beyond the Bailey editor, Ruby Pike, recaps the launch of the newly released book ‘Picturing Peace: Photography, Conflict Transformation, and Peacebuilding’.

Can photography do more than simply document conflict – can it actively shape the path to peace? What role do images play in shaping collective memory in post-conflict societies? And how does visual culture challenge or reinforce dominant narratives of war and peace?

These are among the questions posited by Picturing Peace: Photography, Conflict Transformation, and Peacebuilding, a recently published book that was discussed at a panel event on the 5th of March here at St John’s. The event was hosted by our College Principal, Jolyon Mitchell, alongside academics Tom Allbeson, Pippa Oldfield, Jonathan Long, and Jennifer Wallace, who discussed their fascinating research specialisms and contributions to the volume.

We were all given the opportunity to look at a physical copy as Prof. Mitchell opened the talk with a general overview of the book’s production. With its completion time of a decade, and the erudition of many experts in the field, it is clear that the work that went into this volume is tremendous. A moment was taken to mention and commemorate those who contributed their voices to the book but had sadly passed away before the whole volume had been published.

After this overview had been provided, the microphone was passed to the other hosts, who began to discuss their areas of interest, presenting historically significant photographs and educating us on some key concepts within the academic sphere. (I must clarify that the following descriptions are extremely cursory compared to how well they were described by the experts themselves – I would certainly recommend exploring their works!)

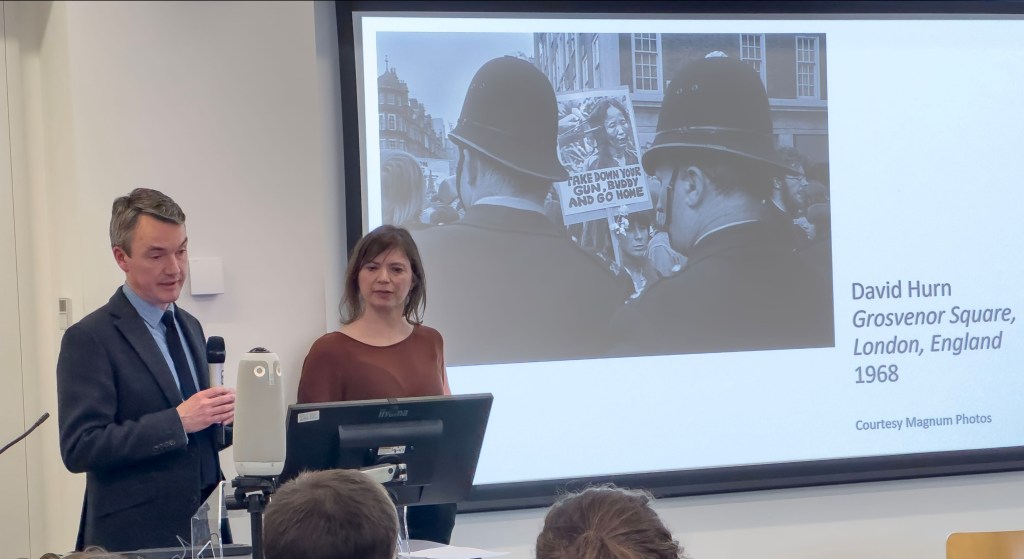

Firstly, Dr. Tom Allbeson, Reader in Media and Photographic History at the University of Cardiff, discussed his chapter Publishing for Peace: Newsworthiness, Authorship and Photobooks of the Vietnam Era. One photograph which I have attached above, on David Hurn’s photograph of protests in Grosvenor Square, has very deliberate positioning, wherein placing an image within another can alter its reception. In this context, press images were recontextualised in countercultural publications to instil radicalism. He expanded on how such images, once produced to serve the mainstream press, were later adopted and transformed by anti-war movements to challenge dominant viewpoints.

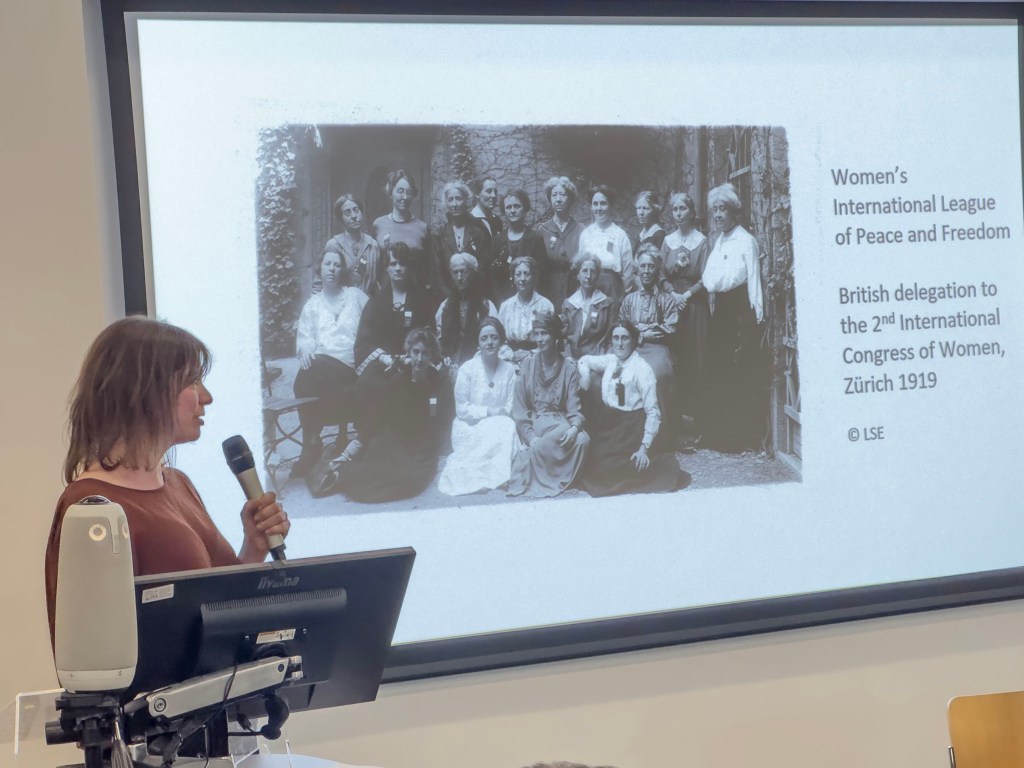

Then, Dr. Pippa Oldfield, a photography curator, historian of photography, and academic at Teesside University, presented her chapter Gender at the Peace Table: Photographic Visualisations of Peacemaking in the First World War. She examined how early 20th-century photographs framed women’s involvement in peace negotiations during and after the First World War, as well as the lasting impact of these depictions on contemporary diplomacy. By bringing attention to archival images of women in impactive positions following World War I, notably the photograph of the British delegation at the 2nd International Congress of Women, it was interesting to hear about how visual culture can either obscure or illuminate the roles played by different social groups.

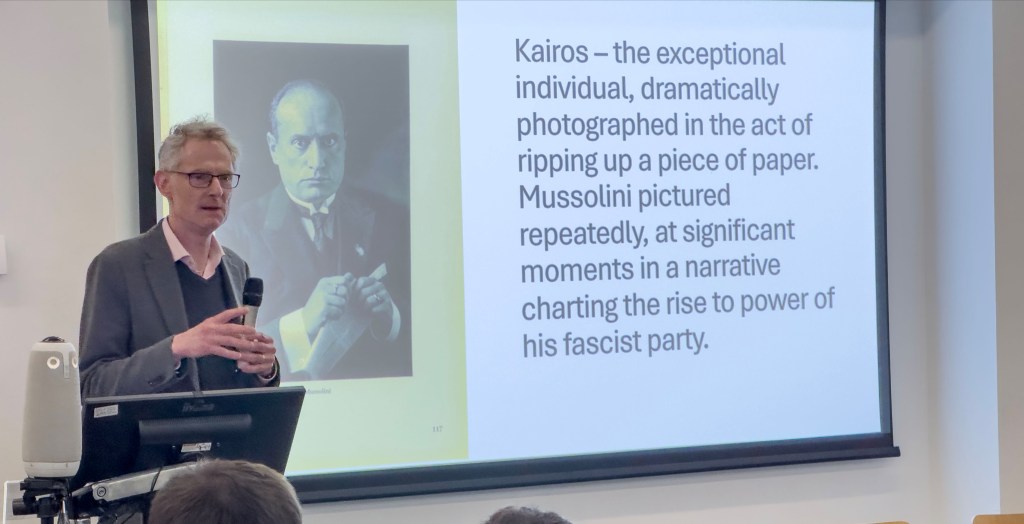

After this, Prof. Jonathan Long, Professor of German and Visual Culture here at Durham, explored Peace and its Discontents: Right-Wing Visions of Peace in the Weimar Republic. He introduced the philosophical concepts of Kairos and Chronos to illustrate competing states – one as an opportune moment (Kairos), the other as an extended process (Chronos), with historical photographic archives representing these. He described Chronos as representing a ‘humanly uninteresting time’ – a period of parliamentary politics marked by the repetitive imagery of men in suits. In contrast, Kairos was depicted as the moment of rupture, exemplified in images of Mussolini dramatically tearing up these photographs, positioning himself as disrupting the ‘stagnation’ of Chronos and leading the Fascist Party into power.

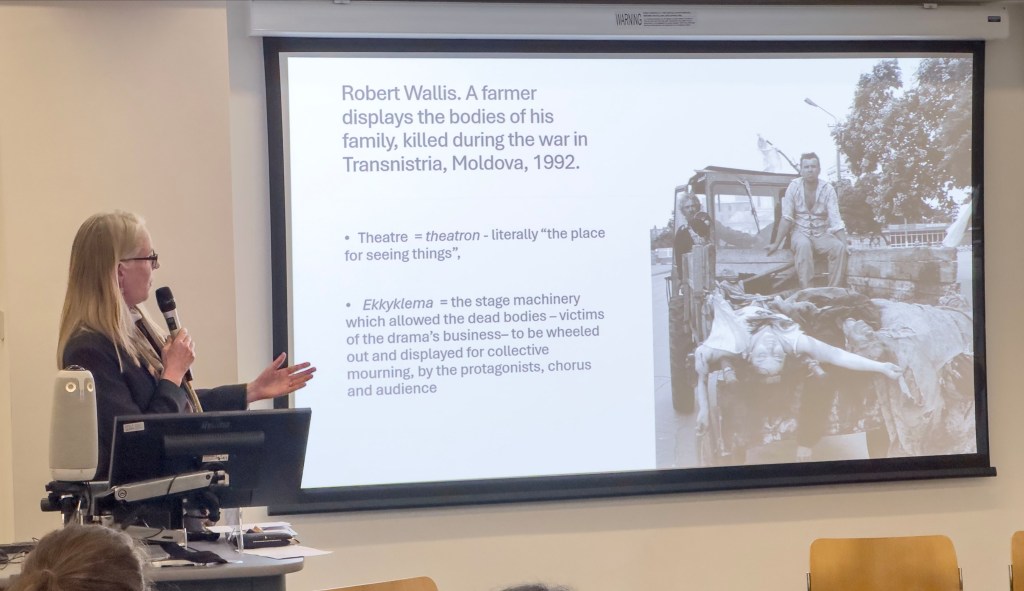

Finally, Dr. Jennifer Wallace, Director of Studies in English at Peterhouse College, Cambridge, discussed Tragedy, Recognition and Photography: Affective Traditions of Witnessing. She explored the ways in which photography functions as a modern extension of ancient theatrical traditions of witnessing. The concept of theatron – literally meaning ‘the place for seeing’ – formed the basis of the idea that photographs, like theatre, invite audiences to bear witness to suffering and, in doing so, shape collective emotional responses. She also introduced the ekklyklema, a stage mechanism used in Greek drama to wheel out the bodies of the dead, drawing a direct comparison to the way war photography confronts audiences with the visual reality of violence.

The panel concluded with a dialogue maintaining that peace cannot be materialised at a whim, nor brought about by any one sweeping decision; it is prudent for us to understand peacebuilding in the very sense of the word, a gradual process that requires sustained effort.

The event was hosted by St John’s College and the University’s Centre for Visual Arts and Culture (CVAC). Upcoming events by the CVAC can be accessed here.

Picture Credit: Robert Wallis